International Disability Day 2020

Living with a disability you can’t see

Categories

- Community

- Auckland

There are two types of disabilities in Aotearoa, New Zealand, those caused by medical conditions, illness or genetic abnormalities and those that result from injury and/or accidents - and we treat them very differently. Last Friday I had my 12 months follow up from a pain management course at Greenlane clinical centre, I caught the bus there because the parking costs for 5 hours was out of my budget. Everyone else had their taxis (and in a few cases, accommodation) paid for by ACC. They had case managers, physiotherapists and significantly more financial help than I could ever hope for. But we were all disabled by pain (theirs, chronic and mine, acute). It was one of those moments when I cried on the phone to my Mum when I got home about the complete unfairness of trying to survive as someone who is chronically ill when it seemed so much more achievable for those who are covered by ACC.

I’ve never broken a bone but have always been jealous of those who have, I started getting sick as an 8-year old (17 years ago now) and I hated that my friends in casts were so easily treated and recognised to be in pain or needing help yet I felt invisible. I quickly realised as a child that bladders and kidneys were not ‘sexy’ organs to have issues with and that it was far more acceptable for people to discuss their asthma or liver problems. No one wanted to hear about years of undiagnosed urinary tract and kidney infections that ravaged my kidneys leaving them scarred and with low function - it was ‘gross’ or ‘yucky’. At 11 I learnt how to self catheterise and then spent the following years hiding it from the world at all costs.

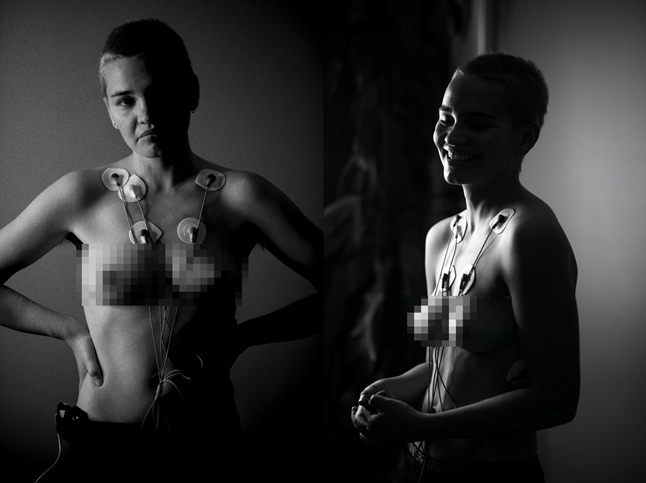

If you saw me at an event photographing, glared at me as I went to use a ‘disabled only’ bathroom or even knew me as an acquaintance - you wouldn’t think I’m disabled.

I look perfectly healthy, I’m slim with an ‘athletic’ body type. Unless you looked carefully for the surgical scars on my abdomen there is nothing to tell you that my body is in a carefully managed turmoil. You wouldn’t know how I precariously balance a range of medication, tweaking them with my doctors to ensure that my blood pressure doesn’t become dangerously high. You wouldn’t see the pain that comes with endometriosis and hundreds of kidney infections. You won’t see the countless hospital trips (I’ve lost track) and even more moments when I should have been there but steadfastly refused to go and instead stayed at home suffering in silence because that was easier than the emotional turmoil of trying to advocate for myself while at my most vulnerable.

Only a select few people in my life see me at my worst, it’s something I hide from the world because it makes people uncomfortable to see someone sick or in pain and not get better.

Over the last few years, I have started talking more openly about my conditions, about the experience of a young woman fighting for herself to be listened to in a medical system that often refuses to. Not because I want sympathy or pity (two things that actually make me extremely uncomfortable) but in the hopes that someone else in my position will feel less alone and that we can start to have more conversations about the way we treat invisibly disabled people.

I’m acutely aware of my privilege as a cis, Pākeha, university-educated woman and that is why I am working on a nationwide advocacy system for young women and non-binary patients across Aotearoa - because I know how hard it is to advocate for myself despite my privileges AND studying medical science for 3 years and that just makes me even more worried for those without those privileges.

Other Stories you might like